COLLABORATIVE COMIC AS BOUNDARY OBJECT

THE CREATION, READING, AND USES OF FREEDOM CITY COMICS

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Overview of context: Freedom City Comics

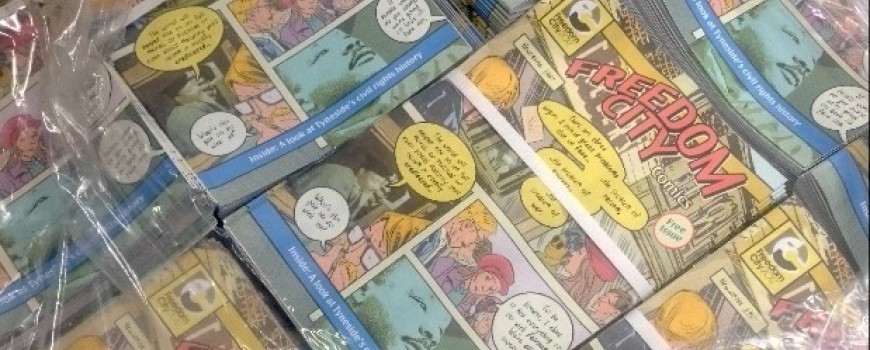

Freedom City Comics (FCC) is a 16-page comics anthology made as a collaboration between seven academic researchers and nine comics creators. Its seven chapters present snapshots of the history of civil rights and politics on Tyneside (geographic area in the North East of England), connected by the overarching theme of freedom. FCC was part of Freedom City 2017 festival, celebrating the anniversary of Dr Martin Luther King Jr’s 1967 visit to Tyneside to collect his honorary degree from Newcastle University. In addition to Dr King’s visit and speech, FCC’s chapters include: freeborn rights, freedom from slavery, political participation, the right to work, and the right to migration and asylum. 37000 free printed copies were distributed in the North East of England, and the comic is free to read online: https://research.ncl.ac.uk/fccomics/.

|

| Image 1: Front cover of Freedom City Comics, Paul Peart-Smith and Brian Ward. |

We locate FCC within the field of applied comics, as a comic with specific content and purposes. The published comic is not an illustration of academic work, nor is it a comic that uses academic research only as a jumping off point. It is credited to both academic researchers and to comics creators equally, as a collaborative work. This is part of a research interest that developed from the first author’s own comics-making practice, initially in parallel with (now intertwined with) her wider work in educational research. In writing from within the project, with a co-author not directly involved in the project, this article is strongly positioned to connect research, practice, and theory. In focusing on FCC as a collaborative comics project, we begin to theorise the collaborative work involved in making, distributing, and reading an applied comic. Using the sociocultural concept of a boundary object is a way to addresses the depth and complexity of these processes. Using the medium and industry of comics as a new focus for that concept in educational research offers opportunities to advance earlier scholarship on boundary objects and boundary crossing, and in so doing begins to connect work on comics as a multimodal medium with wider sociocultural work on multimodality (for which see Bezemer and Kress: 2015). Having introduced this context we will next introduce the concepts of boundary objects and boundary crossing, then use these to explore how FCC could be understood as a multi-layered boundary object.

1.2 Overview of boundary crossing and boundary objects

Our interest is in a boundary object as the site of collaboration between people from unapologetically different domains of expertise. We did not want academic researchers to become comics creators nor comics creators to become academics, but to work together from their existing specialisms. This is consistent with Akkerman and Bakker’s (2011, 34) presentation of a boundary object as an artefact that fulfils a bridging function (Star and Griesemer: 1989) across the borders of distinct domains of expertise. Such domains are evident in the social and cultural practices of different communities, including learning communities, professional roles, and workplaces. Earlier work has focused on moving across boundaries, including Beauchamp and Thomas’ (2011) focus on trainee teachers entering the profession as progressing from one professional identity to another. Such crossing can be a major step that ‘involves going into unfamiliar territories and requires cognitive retooling’ (Tsui and Law: 2007, 1290). FCC was however not about collaborators working together to make a tool to use in their own learning. Instead, our focus on the process of collaboration in making applied comics is largely a precursor to our ultimate interest, namely in how that boundary object (as the object and product of that collaboration) is received by its eventual audiences.

Star and Griesemer’s (1989) account of boundary objects at the intersections of multiple, competing, specialisms within one museum included an awareness of multiple understandings of one object. This differs from our unapologetic acknowledgement that in entering into collaboration one collaborator brought subject knowledge and the other brought creative practice knowledge. For us, both specialisms are held in equal esteem. Our aim was to make a comic with credibility both as a comic and as a research engagement output, with buy-in from all collaborators. This relates to Akkerman and Bakker’s (2011) reading of Star and Griesemer (1989) on boundary objects that satisfy the requirements of both worlds. As such we consider boundaries not as uncrossable chasms but as places for dialogue and learning (Kersuo and Toiviainen: 2011).

In using the wealth of boundary object scholarship from the field of workplace management we must show how FCC differs from workplace settings. In workplace scholarship, boundary objects have been foregrounded as things through which people from different teams within or between organisations work together (Spee and Jarzabkowski: 2009; Sapsed and Salter: 2004), without presuming that knowledge gained through that process will necessarily transfer beyond individual collaborators to their organisations (Gustaffson and Safsten: 2017). We connect FCC to scholarship on boundary objects that are deployed in different contexts to that in which they were created, though with key differences: whereas for Ramsten and Säljö (2012) their adult professional collaborators created a tool for an adult professional audience elsewhere within the same company, our adult professional collaborators were creating a comic for a target audience of children aged 8-14. As such, ours was an outward-facing collaboration with an ultimate aim of creating a cultural product for an external non-specialist audience.

In this early-stage paper we indicate the potential for this comics-research collaboration to be understood as a boundary object, and address these limitations in our final section. We now turn to propose three ways in which FCC could be understood as a boundary object: at its creation, as a collaboration between academic researchers and comics creators; in its evaluation, as a point of contact between the comic’s collaborators and its readers; and in its later educational resource development stage, working with teachers to develop a learning framework to support further use of the comic in education. We will describe and discuss each of these three examples in turn, then identify some emergent themes and potential implications of this conceptualisation.

2: THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

2.1 Making the comic: between academic researchers and comics creators

Each chapter of FCC was made by one academic researcher, typically a historian, and one or two comics creators (named in Appendix I). Our use of the term ‘comics creator’ incorporates planning, writing, drafting, and final artwork as intertwined processes carried out by one or more people. We use it to refer to the individuals who did that writing and drawing rather than the academic researchers with whom they worked, though as we make clear in this article FCC was a comic created as a collaboration. Whereas the process of comics artists and comics writers working together has been addressed by Clarke Gray and Wilkins (2016), our focus is on how academic researchers and comics creators worked together across distinct domains of expertise.

|

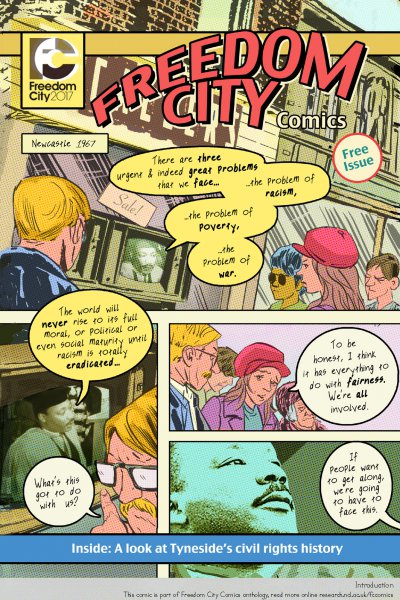

| Image 2: Draft artwork for front cover of Freedom City Comics, Paul Peart-Smith and Brian Ward 2017. |

The comics creators in our team had different prior experience of working on non-fiction comics with subject specialists. Two had worked with us on previous applied comics projects, two had worked on educational projects with other editors, and three had not previously worked on comparable projects. Comparable experience was not a prerequisite for involvement in FCC, though we did look for an interest in the subject matter and/or in using comics in this way. In contrast, none of the academics had previously been involved in making comics. Academics were recruited to the project by the research institute director who commissioned the project. In initial conversations it became apparent that these researchers typically had some familiarity with political cartooning relevant to their subject specialisms or awareness of comics read by their own children, but little of their own past or current interest in comics. They were nevertheless open to embarking upon the project and took time to read comics from our previous collaborations, suggesting the curiosity and courage Carr et al. (2012) highlighted as key attributes for people engaging in boundary crossing. Indeed, it was not inevitable that collaborators would be able to work together, though the successful completion of FCC suggests sufficient congruence of values (Phelan, Locke Davidson, and Cao: 1991) through shared commitment to the project.

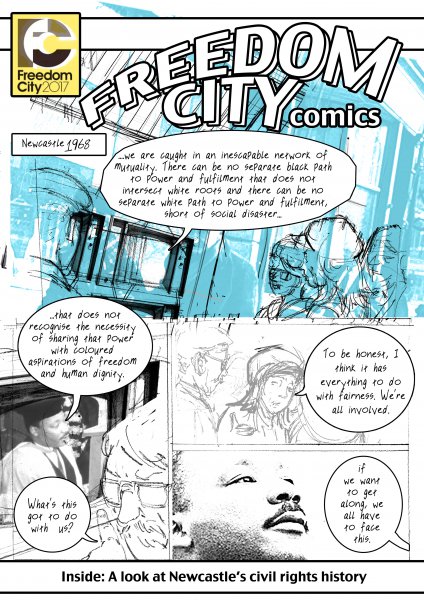

Here follows a brief outline of our collaborative process. As editor, the first author’s initial discussions with academics were distilled into written notes and given to comics creators to prepare a rough draft of a comic. Chapter collaborators then agreed a six-week timescale for a three-stage process: discussing the rough draft, refining a pencilled version of the full chapter, and editorial approval of final artwork of that full chapter. This six-week period is our focus here, though the initial planning and budgeting, and later proofing, printing, distribution, and evaluation took approximately a year in total. Most initial meetings were in person, with subsequent meetings in person, by email, or by video call. The first meeting discussed what the focus of the chapter could be and how much content could be covered within the specified page count (this varied from one to three pages). Historical accuracy was discussed in relation to overall tone and characterisation, in addition to the accuracy of particular likenesses, dates, and details. Discussions about accuracy continued in the second meeting, including a focus on each chapter’s Tyneside connections. Third meetings were typically by email to confirm small changes for accuracy and/or storytelling. Late-stage pages were shared with the comic’s managing editor for guidance on colour saturation and accuracy when printing on newspaper presses, as most comics creators typically worked for digital publication and/or litho and digital printing. Final page setup and print proofing was led by the managing editor.

|

| Image 3: Extract from ‘Freedom from Slavery’, Patrice Aggs and Brycchan Carey, showing FCC’s Tyneside connections. |

The level of editorial involvement varied for each chapter yet suggests a more structured and iterative process than Zurba et al.’s (2017) account of creating videos of choreographed dance as boundary objects. Ours was a collegial process though not always a smooth one, with editorial conversations aimed at balancing ‘good’ artistic representation, historical accuracy, and emphasising the local connections of broader narratives. Engaging in this friction can be a productive part of boundary crossing (Ward et al.: 2011). In our context working through a series of drafts sharpened the focus on what was to be communicated and how to clearly present this to our target audience.

We note two aspects of instability within these processes. First, Akkerman and Van Eijk’s (2013) point that boundaries are evolving and dynamic: our structured process was built on shifting ground. Second, that the boundary object itself evolved through collaboration: our published comic looks different to its initial drafts, but is the same object. Singh (2011) briefly addressed the idea of a boundary object as evolving not static, and our interest in evidence of process advances this further. FCC necessarily changed over time. Initial handwritten notes have a commonality with the finished printed and digital versions of the comic, but differ in appearance, content, and authorship. The back and forth processes of drafting, redrafting, and refining character sketches and comics pages were by definition rough and unfinished: though this messiness later gave way to polished final artwork, it was an essential part of creating each chapter.

The development from messy to pristine parallels Star’s (2010) exciting experience of reading physiologist David Ferrier’s archived notes on an experiment on an ape:

…handwriting occasionally flies off the page, wobbles, and trails off in what clearly is a chase around the room after the hapless animal. The pages, in sharp contrast to my chapel-like surrounds, are stained with blood, tissue preservative, and other undocumented fluids. By contrast... the report of this experiment is clean, deleting mentions of the vicissitudes of this experimental setting. (Star 2010, p.606)

For Star this ‘invisible work… the gap between formal representations’ ( ibid., 606) relates to boundary objects because it was visible only to select participants in that collaboration. For us, openness about rough work was a point of commonality between academic writing and comics creation: the final work often hides the sweat expended in its production. Though we appreciate Singh, Märtsin and Glasswell’s (2013) focus on different ways of working on either side of a boundary, our emphasis is that there was sufficient commonality in drafting practices for our collaborators to work together. Sharing the drafts that might go unshared in solo work was a point of connection in creating FCC, demystifying the creative processes of making a comic, of academic writing, and of collaboration. As we will discuss in section 2.3, including early drafts in our learning framework aimed to make these processes more visible to children. This differentiation begins to suggest how a comic as boundary object might differ from, and thus expand, earlier work on the nature and role of boundary objects.

2.2 Evaluating the comic: between comic collaborators and readers

Universities have boundaries. Despite advances in outreach, widening participation, and civic engagement (for which see Duncan and Oliver: 2017), these borders persist. For every partnership that crosses boundaries there remains someone who is reluctant to walk through a university campus, much less consider studying or working there. As such our decision to distribute the vast majority of printed copies of FCC beyond our university campus built on earlier professional connections with local and regional comic shop and municipal library staff, in addition to Freedom City 2017 festival venues including theatres, galleries, and museums. 23000 comics from our total 37000 copy print run were distributed as inserts in The Crack regional listings free magazine, not through institutional leverage but because The Crack’s editor in chief had read and enjoyed the comic. This regional distribution reflects our target readership of a general young adult and adult audience beyond our core age 8-14 readers, though this core audience remained paramount particularly in developing a coherent approach to the content and language of FCC.

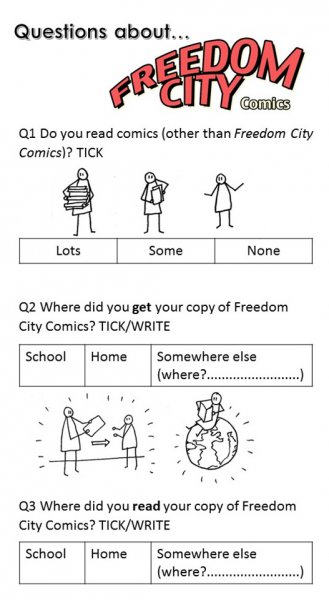

FCC crossed a boundary in its distribution and readership: having been created by academic researchers and comics creators, the finished comic was well received by a range of readers beyond the university. Our evaluation of FCC involved six focus groups. The core groups were three school groups (age 10-13) and one library teen reading group (age 12-13) and, particularly given the civil rights theme of FCC, with attention paid to including different postcode areas (socioeconomic status) and a mix of ethnic groups (summarised as White or BAME Black and Minority Ethnic) without setting quotas for involvement. Two further adult groups were included, acknowledging the wider readership of FCC: a graphic novel reading group and an English language conversation group (age 21 to over 65). The number of participants per group ranged from 6 to 17. This convenience sample recruited through our own professional networks reflects our choice to focus on the Tyneside area, and the reality that pressure on schools including state inspections and exam preparation makes it increasingly difficult to work with schools on projects not tightly linked to the curriculum. All groups received free copies of FCC, and the age 10-13 groups were offered additional time for a ‘meet the editor’ conversation to learn more about the processes of making comics, which teachers and library staff enthusiastically accepted. Each session involved a combination of group discussion and individual data collection using a questionnaire [1] , with the exception of the youngest (age 10-11) group whose responses were recorded on one questionnaire as a headcount of the whole class.

|

| Image 4: Extract from reader feedback questionnaire, Lydia Wysocki/ FCC. |

Compiling the data as frequency tables demonstrated that there were few self-professed comics readers in our sample: only 16 of 86 respondents said they read comics other than FCC. This challenges lingering perceptions that comics readers are somehow a specialised homogenous group distinct from ‘normal’ readers. There is a global industry of specialist comics publishers and retailers, ranging from glossy serialisations to handdrawn and photocopied mini publications. Yet comics are also found in newspapers, textbooks, advertisements, and online: you do not have to go far to encounter a comic. Further findings were positive, with most respondents saying they would recommend FCC to friends (62 of 67 respondents) and to family (56 of 67 respondents). Acknowledging that this convenience sample is not generalizable, it is however worth noting that in evaluating our previous Newcastle Science Comic project (Wysocki 2018) our sample of museum visitors were similarly not self-professed comics readers but nonetheless positive about the comic they were given.

It was through FCC as a published comic that collaborators’ work connected with readers. Children aged 10-13 are rarely the main audience for academic articles and books. Nevertheless when asked what they liked about the art, writing, and content of the comic, respondents did comment on what they liked in the content – the history, as historical research – of FCC. In respondents’ own words:

This is one of the best one because it has more information, it is reliable and trustworthy (library, age 12-13).

I like this one because I like older texts because it shows history is great (school, age 11-12).

Readers were asked to choose their top three chapters by art style, writing style, and historical content. A tally count of responses (Table 1) shows that each chapter of FCC was among someone’s favourites. Finding that no chapter was no-one’s favourite, and that no single chapter was unanimously preferred, supports our use of an anthology format. We used multiple snapshots of history told in multiple styles, rather than a single continuous approach, to appeal to a range of readers’ unpredictable preferences.

|

Chapter 1 |

Chapter 2 |

Chapter 3 |

Chapter 4 |

Chapter 5 |

Chapter 6 |

Chapter 7 |

|

|

Art style |

24 |

28 |

21 |

21 |

13 |

16 |

32 |

|

Writing style |

24 |

18 |

26 |

37 |

17 |

7 |

13 |

|

Content |

14 |

18 |

14 |

22 |

14 |

28 |

21 |

Table 1: Respondents’ favourite FCC chapters by art style, writing style, and content.

In distributing FCC as both a print comic and an online PDF we took a hybrid approach to comics publishing. Whereas Plimmer’s (2016) work on how mobile phone technology can transcend physical and virtual worlds conceptualised the technology as a boundary crossing tool, for us it is the comic as boundary object, in print or digital form, that facilitates this crossing. Though a printed comic differs from a mobile phone the mobility, portability, accessibility, and familiarity emphasised by Sarangapani et al. (2016) remain relevant to FCC, particularly in how an object ‘can comfortably traverse the boundaries of formal and informal learning spaces (schools and homes)’ (ibid., 2). This could have further implications for understanding how a comic as boundary object crosses between formal and informal learning, as a medium in widespread use outside schooling as well as having specific classroom-based uses. There are parallels with Øygardslia’s (2018) finding that computer games in school risk not being seen as learning or as purposeful activity, and with Wallerstedt and Lindgren’s (2016) account of complexity in how boundaries are crossed in the teaching and learning of contemporary music in schools.

2.3 Making and using the learning framework: between comic collaborators and teachers, and teachers and pupils

Through further collaboration with two teachers we created a FCC learning framework. The full framework and resources are available online ( https://research.ncl.ac.uk/fccomics/learningframework/), with a summary of content and curriculum connection provided as Appendix II. This framework focused not on didactic lesson plans but a more flexible enquiry-based approach, providing activities and resources based on each chapter of FCC and linked to the UK National Curriculum for Key Stage 2 (age 7-11) and Key Stage 3 (age 11-14). Both teachers had prior experience with comics: Mike Thompson is a primary school (KS2) teacher and former comic shop manager, and Gary Bainbridge is a secondary school (KS3) Art teacher and comics creator. They were keen to be involved in this project to support the use of comics in education, discussing this as a point of crossover with their current professional identities. Working with teachers who were already aware of the potential for using comics in education was a way to build on their professional credibility to show more teachers how comics can be used in enquiry- and project-based approaches to learning.

In taking an enquiry-based approach (Leat 2017) our framework differs from recent work on comics and literacy development (Wallner 2017) in not only advocating for learning through reading content presented in comics form. We position each chapter of FCC as a springboard for groups’ own projects, identifying specific activities (with resources) and connecting these to the National Curriculum. As mentioned in section 2.1, including rough drafts from each chapter of FCC in our learning framework makes these messy collaborative and creative processes visible to teachers and children. This presents authentic drafts as educational resources that expose and demystify creative processes, for example through activities in which pupils edit the same written text that evolved through our academics’ and comics creators’ collaboration. Our regional focus has been crucial (Leat and Thomas 2018), and though acknowledging that this could limit its direct use by teachers further afield, FCC remains an adaptable model for other comics and curriculum projects.

|

| Image 5: Comparison of draft (left) and final (right) artwork for ‘Activists and Radicals on Tyneside’, John Clark and Matthew Grenby. |

Creating a learning framework positioned FCC at the boundary of collaboration between comics collaborators (comics creators and academic researchers) and teachers. The teachers’ work, with the editor as broker, identified connections between the creative and academic intent of FCC and existing National Curriculum content. It has also benefited these teachers’ own professional development: one teacher used their involvement in this learning framework as evidence in a successful job interview. By articulating these connections our teachers translated the content of FCC into a learning framework written in professional language intended to resonate with other teachers. This presents a further stage of boundary crossing: from our collaborating teachers to other teachers (and through them to pupils) who were not otherwise involved in creating FCC and the learning framework that supports it. Our intent is that these resources are used by teachers not already familiar or confident in using comics in educational contexts, thus enabling more teachers (and more students) to use comics in education. At this stage of the takeup of that learning framework and its impact on those further teachers and students is unknown.

There is a broader point here on the role of brokers in mediating collaborations. Leat and Thomas’ (2018) focus was on curriculum brokers: people external to a given school who enable the bridging discussions between school curriculum leaders and families/communities, working towards the development of localised curricula. In teasing out the roles played by individual brokers in this process they not only uncovered some desired personal attributes for engaging in such work, but also articulated why boundary crossing matters to educational research:

Boundary crossing is located within sociocultural perspectives on learning, which sees participation in communities and sites of practice as the critical medium of learning. Thus transfer of learning is reframed, becoming less a case of transferring knowledge or skills and more related to the facility of moving successfully between contexts. (Leat and Thomas: 2018, 203)

It is this process of moving between contexts that we seek to build on in exploring the role of the comics editor as a broker, addressing both the learning framework as a collaboration with teachers and the initial creation of FCC as a collaboration between comics creators and academic researchers. The first author’s own hybrid identity as both researcher and comics creator means she habitually crosses boundaries between specialised vocabularies and ways of working. As editor she had sufficient knowledge of and credibility in each field to translate jargon and expectations between comics creators, academic researchers, and teachers, in facilitating collaboration between specialised professionals. The editor-as-broker’s task became to facilitate enough collaboration to create the planned outputs, without an expectation that collaborators would exchange roles: there was no intention that comics creators should become historians or vice versa, though such career moves are possible. Whereas Bakx et al.’s (2016) focus was the collaborative creation of boundary objects that narrow the gap between teachers and educational researchers, for FCC this process of mediation meant it was not a worry that the gap between collaborators remained. It was in making boundary objects that collaboration between these two otherwise distinct groups happened, with no expectation of an ongoing relationship beyond the project.

3: LIMITATIONS, IMPLICATIONS, AND NEXT STEPS

In this early-stage paper we have cautiously advanced the claim that an applied comic can be conceptualised as a boundary object, and that this concept can usefully address the depth and complexity of this comics project. We acknowledge that there is further theoretical work to be done. A sociocultural view that language is essential to learning but is not a neutral carrier of meaning (Vygotsky 1978) is pertinent to the integration of visual and verbal languages in the multimodal medium of comics, and as such we intend to further explore work by Engeström et al (1995; Kerosuo and Engeström 2003), moving towards theorising applied comics and how it relates to a sociocultural Activity Theory framework. Further work is needed to align comics as a boundary object with Cultural Historical Activity Theory, which could be taken further still by problematizing assumptions of whose expertise, and what values underpinning that expertise, are prioritised in collaborations: Leonardo and Manning’s (2017) critique of CHAT as the non-neutral White Historical Activity Theory will be relevant, particularly given the civil rights thematic focus of FCC.

In creating FCC our emphasis has been on the wider dissemination of extant academic research and local history, which is distinct from fine art approaches to comics studies where drawing (and other artistic practice) is pursued as research (Miers: 2015). FCC has however been a multi-layered project in which the empirical evaluation and now theorising of the comic as boundary object are themselves aspects of broader social science research. This stratification has particular resonance for understanding what counts as research in comics studies, an inherently interdisciplinary field. We presented two collaborating parties of academic researchers and comics creators as having different prior experience of working with historical research and with comics, and this clarity about where boundaries are (Akkerman: 2011, 22) helps clarify the roles of collaborators as a necessary part of working at and across boundaries (Edwards: 2011, 34). This may be particularly relevant to – or anathema to - scholars who both make and research comics, including the publication of academic research in comics form not as wider dissemination but as primary publications (Sousanis: 2015).

A further point at the fringes of this early-stage paper is about understanding collaborators as members of multiple communities of practice (Wenger: 1998), exploring what this means for specific instances of boundary crossing (Wenger-Trayner et al.: 2017). Boundary crossing can be a temporary process (Ramsten and Säljö: 2012; Edwards: 2011) and making FCC was only one of the many tasks our collaborators were involved in as the rest of their professional lives continued apace. Nor can we assume that collaborators’ roles in a specific project are entirely divorced from other aspects of their lives: as mentioned in section 2.1 some academic researchers’ familiarity with comics came not from their own interest in the medium but from seeing their children read comics.

We have argued that Freedom City Comics can be conceptualised as a boundary object. FCC bridged different boundaries at different stages in its creation, reading, and usage. First in its creation, crossing the boundary between academic researchers and comics creators. Second in its evaluation, crossing boundaries between the comic’s creators and its range of readers. Finally in creating a learning framework it crossed a double boundary: from the comic’s creators to two teachers, then on to our aim of connecting with more teachers and through them their students. There may yet be other boundaries to explore, and more nuanced aspects of these boundaries, as we continue this work with particular attention to the specifics of comics as a multimodal medium and of brokering creative practice collaborations. We look forward to engaging with these strengths and uncovering others as our work theorising applied comics as boundary objects continues.

REFERENCES

AKKERMAN, S., and BAKKER, B. (2011): “Boundary crossing and boundary objects”, in Review of Educational Research, 81, pp. 132–169.

AKKERMAN, S.F., and VAN EIJK, M.. (2013): “Re-theorising the student dialogically across and between boundaries of multiple communities”, in British Educational Research Journal, 39 (1), pp.60-72.

BAKX, A., BAKKER, A., KOOPMAN, M., and BEIJAARD, D. (2016): “Boundary crossing by science teacher researchers in a PhD program”, in Teaching and Teacher Education, 60, pp.76-87.

BEAUCHAMP, C., and THOMAS, L. (2011): “New teachers’ identity shifts at the boundary of teacher education and initial practice”, in International Journal of Educational Research, 50, pp.6-13.

BEZEMER, J., and KRESS, G. (2016): Multimodality, Learning and Communication: A Social Semiotic Frame. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

CARR, M., CLARKIN-PHILLIPS, J., BEER, A., THOMAS, R., and WAITAI, M. (2012): “Young children developing meaning-making practices in a museum: the role of boundary objects”, in Museum Management and Curatorship, 27 (1), pp.53-66.

CLARKE GRAY, B., and WILKINS, P. (2016): “The Case of the Missing Author: Toward an Anatomy of Collaboration in Comics”, in Brienza, C., and Johnston, P. (eds.) Cultures of Comics Work. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

DUNCAN, S., and OLIVER, S. (2017): “Editorial”, in Research for All, 1 (1), pp.1-5.

EDWARDS, A. (2011): “Building common knowledge at the boundaries between professional practices: Relational agency and relational expertise in systems of distributed expertise”, in International Journal of Educational Research, 50, pp.33-39.

ENGESTRÖM, Y., ENGESTRÖM, R., andKARKKAINEN, M. (1995): “Polycontextuality and boundary crossing in expert cognition: Learning and problem solving in complex work activities”, in Learning and Instruction, 5, pp.319–336.

GUSTAFFSON, M., and SAFSTEN, K. (2017): “The Learning Potential of Boundary Crossing in the Context of Product Introduction”, in Vocations and Learning, 10, pp.235-252.

KEROSUO, H., and ENGESTRÖM, Y. (2003): “Boundary crossing and learning in creation of new work practice”, Journal of Workplace Learning, 15 (7/8), pp.345-351.

KEROSUO, H., and TOIVIAINEN, H. (2011): “Expansive learning across workplace boundaries”, in International Journal of Educational Research, 50, pp.48-54.

LEAT, D. (ed.) (2017): Enquiry and Project Based Learning: Students, School and Society, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

LEAT, D., and THOMAS, U. (2018): “Exploring the role of ‘brokers’ in developing a localised curriculum”, in The Curriculum Journal, 29 (2), pp.201-218.

LEONARDO, Z., and MANNING, L., (2017): “White historical activity theory: toward a critical understanding of white zones of proximal development”, in Race Ethnicity and Education, 20 (1), pp.15-29.

MIERS, J., (2015): “Depiction and demarcation in comics: Towards an account of the medium as a drawing practice”, in Studies in Comics, 6(1), pp.145-156.

ØYGARDSLIA, K. (2018): “‘But this isn’t school’: exploring tensions in the intersection between school and leisure activities in classroom game design”, in Learning, Media and Technology, 43 (1), pp.85-100.

PHELAN, P., LOCKE DAVIDSON, A., and Cao, H.T. (1991): “Students’ Multiple Worlds: Negotiating the Boundaries of Family, Peer, and School Cultures”, in Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 22 (3), pp. 224-250.

PLIMMER, C. (2016): “Mobile learning as boundary crossing: an alternative route to technology-enhanced learning?”, in Interactive Learning Environments, 24 (5), pp. 979-990.

RAMSTEN, A-C., and SÄLJÖ, R. (2012): “Communities, boundary practices and incentives for knowledge sharing? A study of the deployment of a digital control system in a process industry as a learning activity”, in Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 1, pp. 33-44.

SAPSED, J., and SALTER, A., (2004): “Postcards from the Edge: Local Communities, Global Programs and Boundary Objects”, in Organization Studies, 25 (9), pp. 1515-1534.

SARANGAPANI, V., KHARRUFA, A., BALAAM, M., LEAT, D., and WRIGHT, P. (2016): “Virtual.Cultural.Collaboration- Mobile Phones, Video Technology, and Cross-Cultural Learning”, paper presented at MobileHCI’16, Florence, Italy.

SINGH, A. (2011): “Visual artefacts as boundary objects in participatory research paradigm”, in Journal of Visual Art Practice, 10 (1), pp. 35-50.

SINGH, P., MÄRTSIN, M., and GLASSWELL, K. (2013): “Knowledge work at the boundary: Making a difference to educational disadvantage”, in Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 2, pp. 102-110.

SOUSANIS, N. (2015): Unflattening, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

SPEE, A.P., and JARZABKOWSKI, P., (2009): “Strategy tools as boundary objects”, in Strategic Organization, 7 (2), pp. 223-232.

STAR, S.L., (2010): “This is Not a Boundary Object: reflections on the origin of a concept”, in Science, Technology, & Human Values, 35 (5), pp. 601-617.

STAR, S.L., and GRIESEMER, J.R., (1989): “Institutional Ecology, ‘Translations’ and Boundary Objects: Amateurs and Professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907-1939”, in Social Studies of Science, 19 (3), pp. 387-420.

TSUI, A.B.M., and LAW, D.Y.K. (2007): “Learning as boundary-crossing in school-university partnership”, in Teaching and Teacher Education, 23, pp. 1289-1301.

VYGOTSKY, L.S., (1978): Mind in society: the development of higher psychological processes , Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard University Press.

WALLERSTEDT, C., and LINDGREN, M. (2016): “Crossing the boundary from music outside to inside of school: Contemporary pedagogical challenges”, in British Journal of Music Education, 33 (2), pp. 191-203.

WALLNER, L. (2017): “Speak of the bubble–constructing comic book bubbles as literary devices in a primary school classroom”, in Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics, 8 (2), pp. 173-192.

WARD. C.J., NOLEN, S.B., and Horn, I.S. (2011): “Productive friction: How conflict in student teaching creates opportunities for learning at the boundary”, in International Journal of Educational Research, 50, pp. 14-20.

WENGER, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity, New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

WENGER-TRAYNER, B., WENGER-TRAYNER, E., Cameron, J., Eryigit-Madzwamuse, S., and Hart, A. (2017): “Boundaries and Boundary Objects: An Evaluation Framework for Mixed Methods Research”, in Journal of Mixed Methods Research, pp. 1-18.

WYSOCKI, L. (2018): “Farting Jellyfish and Synergistic Opportunities: The Story and Evaluation of Newcastle Science Comic”, in The Comics Grid, 8(1), pp. 6-14.

ZURBA, M., TENNANT, P., WOODGATE, R.L. (2017): “A day in the life of a young person with anxiety: arts-based boundary objects used to communicate the results of health research”. in Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research , 18 (3), pp. 1-20.

APPENDIX I: LIST OF FREEDOM CITY COMICS COLLABORATORS

Patrice Aggs, Joan Allen, Ragavee Balendran, Brycchan Carey, Mack Chater, John Clark, Brittany Coxon, Matthew Grenby, Rachel Hammersley, Ian Mayor, Sha Nazir, Paul Peart-Smith, Matt Perry, Brian Ward, Terry Wiley, and Lydia Wysocki.

APPENDIX II: SUMMARY OF FCC LEARNING FRAMEWORK

The full Freedom City Comics enquiry-based learning framework is available online: https://research.ncl.ac.uk/fccomics/learningframework/ . The following tables summarise the activities and resources based on each chapter of FCC, with connections to the UK National Curriculum for Key Stage 2 (age 7-11) and Key Stage 3 (age 11-14).

|

Key Stage 2 |

|||

|

Learning framework section |

Comic chapter |

Learning framework activities |

Curriculum links |

|

1 |

Martin Luther King in Newcastle |

Benday dots, light frequencies, colour |

Science, Art, Citizenship, History, Politics |

|

2 |

Freeborn Rights: what’s fair? |

Fairness, rules, making yourself heard, printmaking techniques |

Writing, Literacy, Citizenship, Art |

|

3a |

Equiano’s visit to the North East |

Timeline of events, stage play, maps and distances |

Reading, Writing, Literacy, History, Maths |

|

3b |

Douglass’s friends in the North East |

Researching biographies, researching anti-slavery, modern slavery |

Reading, Writing, Literacy, History |

|

4a |

Miners’ mass demonstration for the right to vote (Joseph Cowen) |

Big numbers, rounding, estimating crowd sizes, storyboarding plans for a video, caricature |

Reading, Writing, Literacy, History, Maths, Citizenship, Art |

|

4b |

Emily Wilding Davison and the Women’s Suffrage Movement |

Evaluating sources for trustworthiness, voter turnout, plotting data on a graph |

History, English, Maths, Citizenship |

|

5a |

The Jarrow March |

Informal writing, formal writing, methods of transport, planning a route, calculating distances |

Writing, History, Geography, Maths |

|

5b |

Ellen Wilkinson MP |

Editing written work, use of colour for emphasis, international contexts |

Literacy, History, Art |

|

6 |

A new home by the sea |

Basque Children’s Committee, Spanish Civil War refugees, seasickness, balance, exploring different opinions |

Science, Writing, Drama, Art |

|

7 |

Activists and radicals on Tyneside |

Prioritising information, researching, biographies, posters and banners in history |

Reading, Art |

|

8 |

Jobs in publishing |

Inferring meaning from evidence, roleplay, heroes, calculating printing costs, planning a project |

Reading, Maths, Careers |

|

Bonus activity |

All chapters |

Our readers’ questionnaire was part of the initial evaluation of Freedom City Comics. It’s also a reading and discussion activity in its own right! |

PSHE (Personal, Social, Health and Economic Education), English, Maths |

|

Key Stage 3 |

|||

|

Learning framework section |

Comic chapter |

Learning framework activities |

Curriculum links |

|

1 |

Martin Luther King in Newcastle |

Plan and design a front cover, identify and use different types of text, comparing genres, comparing video and written text |

Art, Media, English |

|

2 |

Equality before the law |

Summarising information, writing in different forms of English, storyboarding to plan a narrative, printmaking techniques, phonetic alphabet |

Art, English, Modern Foreign Languages |

|

3 |

Freedom from slavery |

Boycott tactics, biographies of abolitionists, formal letter writing, speechwriting |

History, English |

|

4 |

The right to political participation |

Comparing achievements, public art, monuments and controversy, writing a persuasive letter, comparing historical and contemporary viewpoints |

History, English, Drama, Media, Art |

|

5 |

The right to work |

Sequencing events, planning and editing a narrative, estimating distances, calculating distances, promoting a cause |

English, Maths, Media, PSHE, History, Art |

|

6 |

The right to migration and asylum |

Exploring different responses to migration and asylum, writing from a specific point of view, adapting written work into a comic |

RE/Ethics, Maths, Geography, PSHE, History, English, Art |

|

7 |

Activists and radicals on Tyneside |

Arranging a timeline of events, researching biographies, identifying artistic influences |

Art, History, Maths, PSHE |

|

8 |

Meeting your hero |

Conversations with someone you admire, researching work by artists, planning what you want your work to communicate |

English, Drama |

|

Bonus activity |

All chapters |

Our readers’ questionnaire was part of the initial evaluation of Freedom City Comics. It’s also a reading and discussion activity in its own right! |

PSHE, English, Maths |

NOTES

[1] This questionnaire is itself partially in comics form, and is available as part of the FCC learning framework: https://research.ncl.ac.uk/fccomics/learningframework/